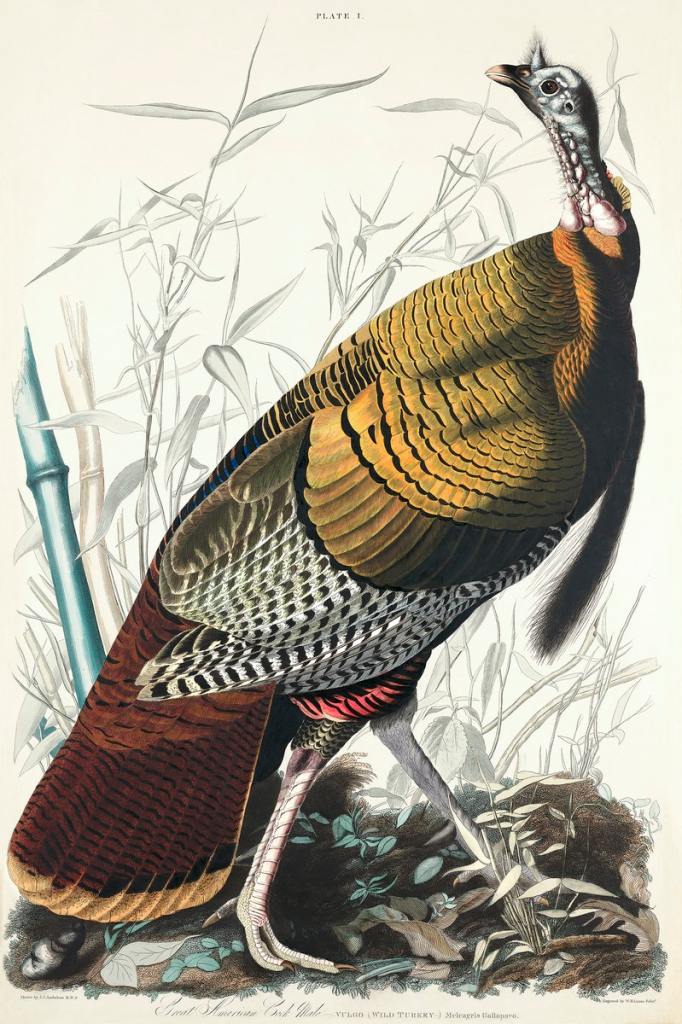

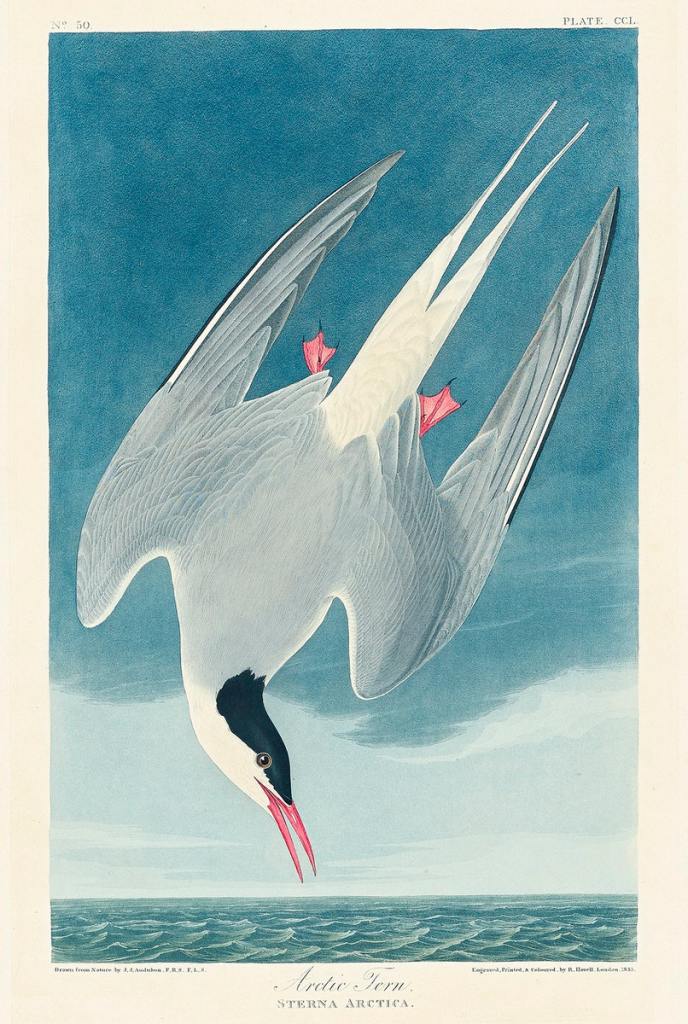

I wrote a short post recently about John James Audubon in later life. I thought I’d spend some time now trying to understand how he was able to complete his most famous work, The Birds of America and its companion Ornithological Biography. Together, they run to nine volumes, thousands of pages of text, and 435 life-size, hand-painted illustrations. I discovered three key elements to Audubon’s success, all of which he worked hard to develop over the course of many years.

First, Audubon mastered his craft. From boyhood, he loved birds and loved to draw birds. By age 20, he had started collecting and drawing his own specimens. He also collected books by famous ornithologists like Alexander Wilson, Charles-Lucien Bonaparte, and François Levaillant, from whom he gleaned valuable ideas like drawing his birds lifesize. As a 25-year-old in 1810, he wrote of his joy in exploring the wilderness of Kentucky, shooting birds and drawing them, his days “happy beyond human conception.” The ability was always there and so, too, was the constant drive to learn more about birds and to hone his skill as an artist.

Audubon’s painting of Passenger Pigeons. Although now extinct, there were billions in North America in 1813. It was around that time the birds swarmed over Audubon in Kentucky, so thickly that “the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow.” Image/Audubon.

You’ll notice that Audubon mentioned shooting birds. Ironically, killing them was the only way to draw them accurately. Otherwise, they hopped around or flew off mid-sketch. Audubon developed clever ways to hang and pose freshly killed specimens with wire and string so they looked alive and in motion. When you see “Drawn from Nature” in tiny script in the lower left corner of Audubon’s paintings, this is what he meant.

Beyond artistic skill, Audubon purposely cultivated an outward appearance of ruggedness. He referred contemptuously to “closet ornithologists” who drew from stuffed specimens in the comfort of their rooms, or who gathered details from others’ drawings. Audubon revelled in the harsh conditions of nature, of crawling and climbing to see the birds for himself in their natural habitats. The persona he crafted of an all-American woodsman was real and hard earned, and he believed it gave him the credibility to be taken seriously as an ornithologist.

By 1826, Audubon had produced hundreds of life-sized watercolor paintings that he proposed to publish in book form. Because of the printing technology available at the time, achieving his vision would be an enormous task requiring the efforts of an entire team of artisans.

Copperplate printing was the standard method of the day. Each of Audubon’s paintings would need to be traced onto paper, then transferred to copper plates through a complex process of chemical and manual etching. Against the plates, textured and inked, heavy paper would be pressed to produce an outline. Colorists would take over with brush and paint to recreate the hues and shades of Audubon’s original works. The quality of the finished product depended on the expertise of the crew, which could easily number into the dozens.

Audubon found no one in the United States prepared to take on such a big job. He finally found an engraver in London willing to share the risks. And risks there were, like the fallout from a flock of pigeons flying overhead. One risk was the sheer size of the book. Audubon’s insistence on lifesize renderings of hundreds of birds, plus descriptive text for each, meant the book likely would be the largest ever published. Another challenge was the steep price. Audubon expected the complete work to go for around $1000, twice what a skilled artisan made in a year and a little over $26,000 today. Still another issue was a British copyright law that mandated each of nine national libraries receive a free copy of every book published.

The way Audubon handled these challenges is the final element of his success. Audubon the artist and woodsman turned out to be a hard-nosed businessman. The lessons learned over decades of supporting himself as a painter helped. Just as importantly, Audubon was an astute observer of people as he was of birds, and what he gleaned over the years helped him now to understand them as consumers.

To offset the price, he targeted institutions with deep pockets, like universities and scholarly societies. When he sold to individuals, he chose only men of verifiable wealth who spent their money wisely–i.e., they were likely to have money to spend for years to come. That was important because to further mitigate the price, he decided to sell the book in pieces over several years, five illustrations at a time. Here Audubon made another astute business move. He knew buyers would place the highest value on the largest birds and possibly stop their purchases once those had been collected. So Audubon included just one large bird in every group of five. To acquire the best illustrations, subscribers had to buy the entire set.

Audubon tackled the copyright conundrum by splitting the book into separate collections. The Birds of America would include only illustrations and no words, which Audubon intended to argue did not meet the definition of a book. I’m sorry that I haven’t been able to learn if this reasoning actually worked, but I’ll go on the assumption that no historical news is good news. All the text and stories he consigned to a second book called Ornithological Biography. Since OB was of normal size, and thus cheaper to publish, he had no problem giving a few copies away to libraries. The Birds of America was a different matter. Audubon later estimated the book cost him $115,000 to produce, over $2.1 million today. With a publication of fewer than 200 copies, that represented more than half of what Birds brought it. (A later edition, smaller in physical size and produced by cheaper means, did make Audubon rich.)

Audubon aggressively sold copies of the books over the next several years while continuing to collect and paint birds. The last illustrations from The Birds of America shipped to subscribers in 1838 and the final volume of Ornithological Biography appeared the following year, almost 20 years after he had started collection drawings. Audubon’s great work was finished and his fame secured.

Works Cited

“The Birds of America.” Wikipedia.

“John J. Audubon’s Birds of America.” Images with accompanying text from Ornithological Biography. Audubon.org.

Nobles, Gregory. John James Audubon: The Nature of the American Woodsman. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 2017. Kindle.

–“The Myth of John James Audubon.” Audubon Magazine. 31 July 2020.

Partridge, Linda Dugan. “By the Book: Audubon and the Tradition of Ornithological Illustration.” Huntington Library Quarterly , 1996, Vol. 59, No. 2/3 (1996), pp. 269-301. JSTOR.org.

Rhodes, Richard. “John James Audubon: America’s Rare Bird.” Smithsonian Magazine. 1 Dec 2004

Sibley, David. “How James Audubon Captured the Romance of the New World.” Smithsonian Magazine. 13 Nov 2013.

I need to come visit this blog more often! Your content is amazing 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike